Science & Tech

Abby Ohlheiser

Jan 13, 2017

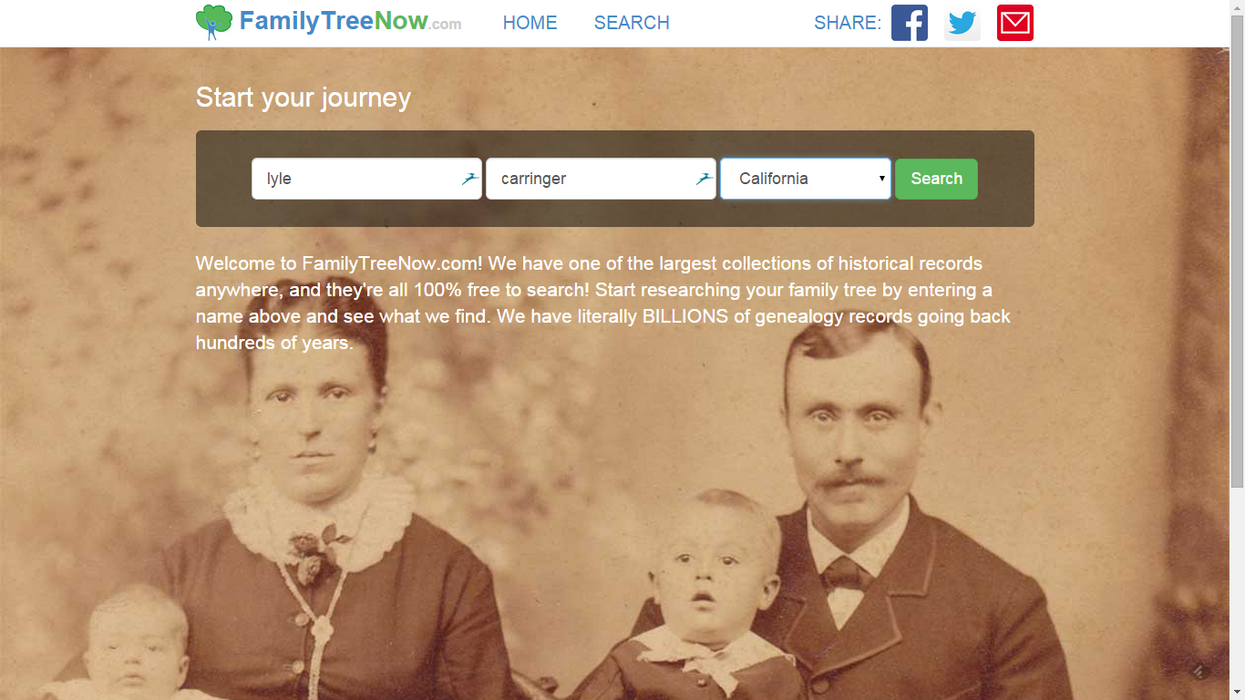

Early Tuesday morning, Anna Brittain got a text from her sister: Did she know about Familytreenow.com? The relatively unknown site, which presents itself as a free genealogy resource, seemed to know an awful lot about her.

“The site listed my 3- and 5-year-olds as ‘possible associates,’ ” Brittain, a 30-year-old young-adult fiction writer in Birmingham, Ala., told The Washington Post on Tuesday. Her sister, a social worker who works at a child advocacy center, found the site while doing a regular Internet footprint checkup on herself. “Given the danger level of my sister’s occupation,” Brittain added, the depth of information available on the genealogy site “scared me to death.”

There are many “people search” sites and data brokers out there, like Spokeo, or Intelius, that also know a lot about you. This is not news, at least for the Internet-literate. And the information on FamilyTreeNow comes largely from the public records and other legally accessible sources that those other data brokers use. What makes FamilyTreeNow stand out on the creepy scale, though, is how easy the site makes it for anyone to access that information all at once, and free.

Profiles on FamilyTreeNow include the age, birth month, family members, addresses and phone numbers for individuals in their system, if they have them. It also guesses at their “possible associates,” all on a publicly accessible, permalink-able page. It’s possible to opt out, but it’s not clear whether doing so actually removes you from their records or (more likely) simply hides your record so it’s no longer accessible to the public.

Unusually for a site like this, FamilyTreeNow doesn’t require a fee, or even the creation of an account, to access those detailed profiles (assuming, of course, that person hasn’t already opted out). Lexis Nexis, for instance, can also aggregate tons of public records to create an in-depth profile of a person. But that service is cost-prohibitive to most people who don’t have access to the site through an institutional subscription.

Sure, a free database aggregating thousands of U.S. public records could be beloved by genealogy hobbyists across the country. But the site is also extremely useful to those who might want to harass or physically harm someone else — and that, it seems, is what is freaking a lot of people out about it.

After reading the text from her sister, Brittain pulled up her own profile and immediately opted out of having her information included on the site. Then she composed tweets, warning others and providing detailed instructions on how to do the same. The top of her thread on FamilyTreeNow had thousands of retweets by the end of the day.

A similar warning about FamilyTreeNow also popped up on “Enough is Enough” and “Survive the Streets” this week, both popular Facebook groups about law enforcement officer safety. One post, which begins, “OFFICER SAFETY ALERT” warned that the site could be used by individuals who want to target the families of police officers. That post had more than 10,000 shares by Wednesday morning. As Snopes noted, the site doesn’t specifically note whether an individual is a member of law enforcement or not.

Several Washington Post reporters checked their own listings on the site in response to these warnings. The listings largely appeared to be thorough and accurate — although not perfect in every case.

My listing had accurate home addresses going back several years, my correct age and birth month, and links to the names, ages and profiles of my family members. It also flagged two “possible associates” for me, people who FamilyTreeNow believed might be connected to me somehow, based on its aggregation of public records. Those “possible associates” were my former roommate and my ex-boyfriend.

I also opted out; within an hour or so of doing that, my listing was no longer accessible. You can still see that there’s a listing for me on FamilyTreeNow when you search for my name, but it doesn’t actually let you click on it to learn more. It isn’t clear whether “opting out” eventually removes your personal information from their database, or whether it just prompts the site to block access to it.

If you’d like to opt out, by the way, go here and follow the steps. Some of my colleagues had trouble getting their opt-out requests to go through the first time; and it seems there’s a cap on how many records you can opt out in a single day. Others had trouble trying to get an opt-out to work on mobile and had to switch to desktop. The site said those listings will go away within 48 hours.

Opting out of FamilyTreeNow is a good start to any sort of Internet privacy checkup. But it’s worth noting that it’s just that: a start. There’s a lot more work you’d have to do to get control of your personal information on the Internet. Journalist Julia Angwin compiled an exhaustive list of all the data brokers she could find a couple of years ago, and tried to opt out of having her information included in each of their databases. Fewer than half of the 212 data brokers she identified accepted requests for opt-outs, she wrote in a blog post that gives detailed instructions on how to remove yourself from many of these services.

I tried to reach Dustin Weirich, the Sacramento-based entrepreneur who listed himself as the founder of FamilyTreeNow on his LinkedIn page and is the only manager listed in California public records for Family Tree Now LLC. I hoped that speaking to him would help me understand why this database was created in the first place.

But Weirich, or any representative of the site, did not respond to an emailed request for comment to multiple addresses associated with FamilyTreeNow or Weirich’s other listed businesses. One listed phone number for a business associated with Weirich went to a generic Google Voice voice mail; additional phone numbers listed for Weirich appeared to be disconnected. Over the course of Tuesday, Weirich’s LinkedIn page and FamilyTreeNow profiles also became inaccessible to the public.

Based on its Internet history and public records, the company appears to be a few years old. One complaint about its living people database goes back to 2015, for instance. The site has a Twitter account and a Facebook page, but both appear to have been inactive for some time.

Although FamilyTreeNow isn’t unique, the timing of Brittain’s warning about the site — along with the depth and accessibility of the information available there — really hit a nerve with a lot of people who saw it. One possible reason: “Twitter is a dangerous place right now for marginalized groups,” Brittain said. She’s seen it in the young-adult fiction community lately, where “women, minority groups, and marginalized people are targets of online abuse and threats almost daily, and this level of information could be particularly dangerous for them.”

“Perhaps,” she said, “the software engineers didn’t quite puzzle together the kind of monster they were creating.”

Brittain said that she’d gotten a lot of replies, particularly from people in their teens and early 20s expressing shock that it was even possible for people to access basic information like this. Her warning may have resonated, she guessed, because people are more on edge about online abuse right now.

“Online trolls have lurked around the underbelly of the Internet since ever,” she said, “but I’ve never seen anything like the online abuse targeted toward women, minority groups, and marginalized people than what I’ve witnessed since the election.”

Washington Post

Top 100

The Conversation (0)