Harriet Brewis

Feb 15, 2025

USF receives grant to help forecast sargassum

Fox - 13 News / VideoElephant

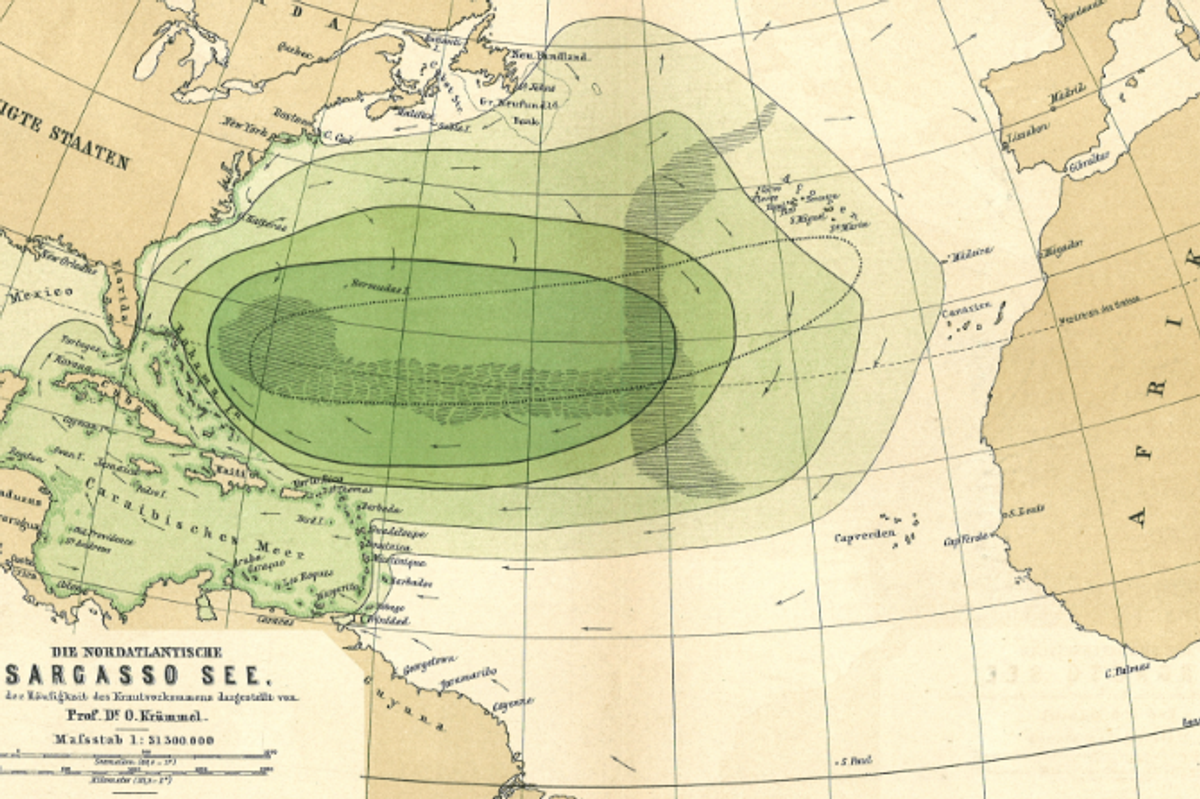

Forget the seaside, there’s one body of water on Earth that doesn’t touch a single coastline.

The region, located in the North Atlantic Ocean is called the Sargasso Sea and it’s characterised by its unique boundaries.

Rather than land, it’s defined by ocean currents, so there’s no Sargasso beach to hit.

Not that you’d necessarily want to. The sea is blanketed in a foul-smelling brownish-yellow, seaweed (called Sargassum) and has become home to a nightmarish manmade island, dubbed the North Atlantic Garbage Patch.

And yet, it remains a site of real ecological, historical and even cultural significance.

A special organisation set up to protect the exceptional sea hails it as a “haven of biodiversity” which plays a crucial role in the wider North Atlantic ecosystem.

The Sargasso Sea Commission notes that endangered species of eels go to the sea to breed, while whales – most notably sperm and humpbacks – migrate through it, as do tuna and other types of fish.

It is also key to supporting the life cycle of a number of threatened and endangered species, including the Porbeagle shark and several types of turtles.

To borrow the words of renowned marine biologist Dr Sylvia Earle, it is a “golden floating rainforest”.

And the sea isn’t just legendary in the eyes of oceanographers, it is the stuff of folklore, too.

Christopher Columbus first documented encounters with its strange mats of Sargassum in his expedition diaries back in 1492.

He wrote of his sailors’ fears that the seaweed would entangle them and drag them to the ocean floor, or that the windless calms (doldrums) that they faced in the Sargasso Sea might prevent them to returning to Spain.

Such fears became part of the sea's lore for centuries, with its notoriety further boosted by its association with the infamous Bermuda Triangle.

The triangle – known for being an area where planes and ships would suddenly disappear for no reason – is located in the the southwest area of the Sargasso between Bermuda, Florida and Puerto Rico.

The sea exists thanks to four currents: the North Atlantic Current to the north; the Canary Current to the east; the North Atlantic Equatorial Current to the south; and the Antilles Current to the west.

These circular currents, called ocean gyres effectively trap the body of water within them, resulting in what Jules Verne described in ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea’ as “a perfect lake in the open Atlantic.”

And yet, these days, this “lake” is far from perfect.

The Sargasso is now under real threat from shipping – including underwater noise, damage to Sargassum mats, and the release of chemicals, overfishing, pollution from floating debris and, of course, climate change.

Because of the ocean gyres’s circulating motions, plastic swirls into the sea, joining the hideous garbage patch that has formed there.

This gigantic memorial to humankind’s destructive ways is estimated to extend for hundreds of kilometres and to have a density of 200,000 pieces of rubbish per kilometre squared.

And things are only getting worse.

A new study, published on 8 December, found that the sea is warmer, saltier and more acidic than it has ever been since records began in 1954, and that this could have a serious and far-reaching impact on other ocean systems.

The report’s lead author, chemical oceanographer Nicholas Bates, warned that the ocean is the warmest its been for “millions and millions of years”, which could lead to serious changes to local marine life and the global cycling of water – “where it rains or where it doesn’t.”

Speaking to LiveScience, Prof Bates admitted that global warming may have reached a point from which there's potentially no return for quite a long time."

This article was originally published on December 28, 2023

Sign up for our free Indy100 weekly newsletter

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings

Top 100

The Conversation (0)