News

Travis M. Andrews

Nov 21, 2016

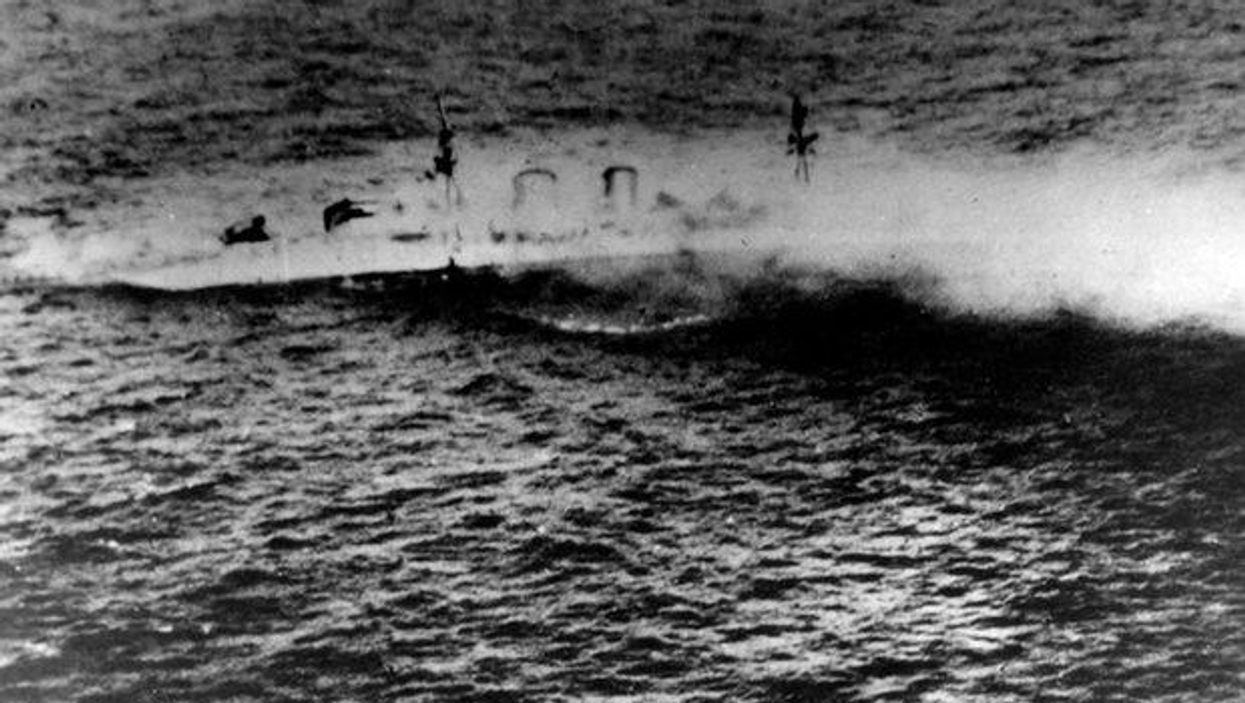

The Royal Navy heavy cruiser HMS Exeter, which sank during an operation in the Java Sea on 1 March 1942

US Naval History and Heritage Command

The HMS Exeter, a heavy cruiser in the Royal Navy, weighed nearly 10,000 imperial tons.

The slightly smaller HMS Encounter and the destroyer HMS Electra flanked the great beast of a ship as the trio sailed near Indonesia.

On Feb. 27, 1942, they entered the Java Sea, which lies between the islands of Java and Borneo.

Along with them were Dutch ships HNLMS De Ruyter, HNLMS Java and HNLMS Kortenaer and many, many others.

There, these six ships — along with those of other Allied Forces, including Americans — engaged in a long and grueling World War II battle with a Japanese fleet. According to the Guardian, it was one of the “costliest sea skirmishes for the allies” and helped enable the Japanese to occupy the Dutch East Indies.

Many sailors died in the battle. Those six ships, for example, sank to the bottom of the sea. Perishing along with their vessel were about 2,200 people, Dutch News reported.

The ships lay in their watery graves, about 230 feet deep, for many years before human eyes witnessed them again. In 2002, a group of amateur divers discovered the wreckage resting peacefully at the bottom of the sea.

The area was declared a sacred war grave, Time reported.

“The Battle for Java Sea is part of our collective memory,” Dutch Defense Minister Jeanine Hennis said, according to the Dutch News.

The wrecks bear silent witness to the tragic events and form a backdrop to the many stories about the terrors of war and the comradeship between crew.

With the battle’s 75th anniversary quickly approaching, a new expedition of divers set out to film the missing ships for a commemoration of the historic day.

When they reached the spot, though, researchers were shocked by what they found. Rather, they were shocked by what they didn’t find.

The ships were almost entirely gone.

Poof.

The HMS Exeter, that monolith of a ship, and the smaller HMS Encounter were nearly completely gone.

According to the Guardian, researchers used underwater sonar equipment to create a 3D map of the sea floor, where the wreckage had been. But where the debris “was once located, there is a large ‘hole’ in the seabed.”

A “sizable section” of the HMS Electra remained, but it, too, was mostly missing. Also disappeared was a 298-foot American submarine, the USS Perch.

Meanwhile, Hennis, the Dutch defense minister, told lawmakers that two of the three Dutch ships had also vanished, and the third was mostly missing.

All of which raises the question, how do several ships simply disappear?

The most agreed-upon answer, in this case, appears to be scavengers with hopes of selling the metal from the shipwrecks for profit. In total, the Guardian reported, the metal could be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. The propellers alone, many of which are made from phosphor bronze, are priced at almost $2,500 a ton.

If scavengers did indeed steal the wreckage, they would have broken international law, Andy Brockman, an archaeologist and researcher in maritime crime, told the newspaper. The ships are the legal property of the country to which they originally belonged.

But, as the BBC stated, “salvaging the wrecks would have been a huge operation.”

The ships were about 230 feet underwater and about 60 miles offshore. Some experts claim that they would too difficult to salvage.

“It is almost impossible to salvage this,” Paul Koole of the salvage specialists Mammoet told Algemeen Dagblad. “It is far too deep.”

But it has become increasingly common around Indonesia, where hundreds of ships sank during World War II.

“It’s like a cottage industry, apart from the fact the illicit salvage boats are dealing with substantial wrecks. Basically they use explosives and grabs to rip things apart,” Brockman told the Guardian. “You get basis steel. In a single engine room you have a lot of nonferrous metals, copper and brass, which have a premium on the scrap metal market.”

The explosions would be small and mostly undetectable, especially that far offshore, one expert said.

“It is not like a huge explosion like you see on TV. It’s basically fairly contained but enough to break apart the vessel and if you do it a few times, you can just fish out the pieces,” Bas Wiebe, commercial manager of salvage company Resolve’s Asia operations, told the BBC.

Given that, some experts told the BBC that scavengers could have “nibbled away” at the ships for years, going mostly unnoticed.

"If time is not of the essence, you have a barge and equipment, you could just nibble away,” said one expert who declined to be named.

The British Ministry of Defense said the British government has contacted Indonesian authorities, requesting that they investigate the missing ships and take “appropriate action to protect the sites from any further disturbance.”

“The desecration of a war grave is a serious offence,” the British Defense Ministry said in a statement obtained by the BBC.

Many lives were lost during this battle and we would expect that these sites are respected and left undisturbed without the express consent of the United Kingdom.

Theo Doorman, the 82-year-old son of Rear Adm. Karel Doorman, one of the battle’s leaders, was on the expedition that discovered the ships were missing. He was shocked when the first sonar images returned, showing the ships were gone.

“I was sad,” Doorman told the BBC. “Not angry. That doesn’t get you anywhere. But sad. For centuries it was a custom not to disturb sailors’ graves. But it did happen here.”

The Indonesian navy claimed it wasn’t aware of any scavenging that might have occurred.

"To say that the wreckage had gone suddenly doesn’t make sense,” Col. Gig Sipasulta, an Indonesian navy spokesman, told the BBC. “It is underwater activities that can take months, even years."

Copyright: Washington Post

More: A hiker wore a bandana for sun protection. Then she found a note on her car

Top 100

The Conversation (0)