News

Bethan McKernan

Jul 13, 2016

Picture: Aenne Chene/Fawcett Society

"This is the feminist revolution in the same way that the Charge of the Light Brigade was a military triumph.”

So wrote Laurie Penny of the Tory leadership race, just before Andrea Leadsom dropped out.

Presumptive prime minister Theresa May will on Wednesday become only the second ever woman to hold that office, and she has in some respects done much for other women - championing equal pay and widening access to the Conservative party for women and minorities.

However, many are critical of the new PM's stance on austerity, immigration, and several other issues which have uniquely adverse effects for women.

It's worth noting that simply because she's a woman, May's actions as prime minister will be judged with added performance pressure. (On Tuesday morning, female candidate for leader of the Labour party, Angela Eagle, was asked on the Today programme whether she would cry in front of Putin.)

A University of Exeter study first identified a phenomenon known as the 'glass cliff' in 2004 - that women are more likely to be put in leadership roles during periods of turmoil, when their chances of failure are higher.

The authors looked at FTSE 100 companies before and after appointing new board members, and found that companies that appointed women were more likely to have performed badly in the previous two quarters. They found application for the theory in several other arenas, including politics.

On top of that, a woman at the top doesn't reflect gender parity in the rest of a system.

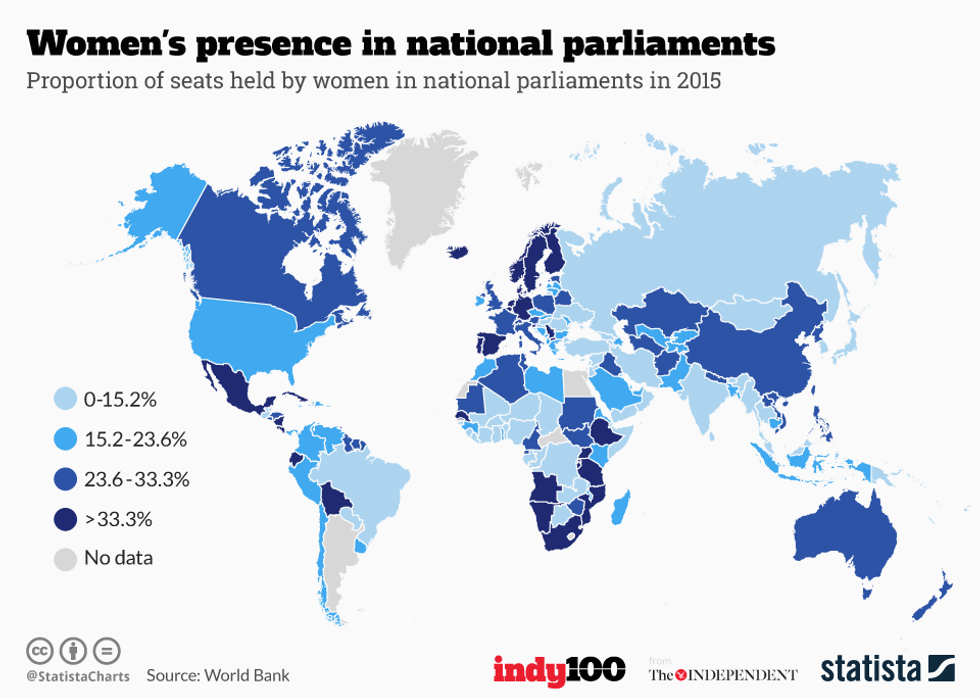

Just look at this chart from Statista, which shows how many women held seats in parliaments across the world in 2015:

The 2015 election was the most gender balanced ever - 29.4 per cent of the UK's MPs are currently women, or 191 out of 650.

We are left in the dust by other countries around the globe for political gender representation though. The World Bank ranks us as 43rd out of 186 countries. Rwanda's parliament is 63 per cent women, and Bolivia's is 53 per cent.

In the UK, at the current rate of progress, we could have gender parity by 2030 - but only if we're lucky.

That relies on the same 6.6 per cent gain from 2015 being made in every election up until then, and without all-female shortlists and with the 'incumbency blocker' effect in safe seats, that's very unlikely.

We may have another female prime minister, but we've still got a long way to go.

More: Remembering that time Theresa May blamed a cat for high immigration

More: Who will be in Theresa May's cabinet according to the media

Top 100

The Conversation (0)