News

Evan Bartlett

Feb 12, 2015

Our tour guides for the evening: ActionAid's Tom Barns and Natasha Adams

Traipsing around the streets of London on a cold Tuesday evening in the middle of February talking about the complex workings of tax avoidance might seem a rather odd thing to do. And well it probably is.

But whether it's legal tax minimising measures, like those of the company that David Cameron’s wife works for, or the revelations leaked this week of widespread and systemic tax evasion by some clients of HSBC's Swiss subsidiary, tax is big news at the moment.

Tax evasion and avoidance has left a huge hole in the public coffers, not only in Britain but in developing countries across the world too.

So here I am, on that aforementioned cold Tuesday night in February, embarking on a tax avoidance tour with activists from ActionAid to find the answer to the all-important question: how do big businesses get away with paying less tax than the rest of us and what can we do about it?

What's the situation?

In a 2013 study, ActionAid found that 98 of the FTSE 100 companies - the 100 most valuable companies listed on London's stock exchange - regularly use tax havens.

As we wander through the backstreets of Mayfair - one of London's most upmarket neighbourhoods - our guides, Natasha and Tom, point out a consultancy firm that boasts of offering its clients "structured wealth solutions". Expensive lawyers and accountants like these find legal loopholes for their clients to save them millions, if not billions, of pounds through the use of tax havens.

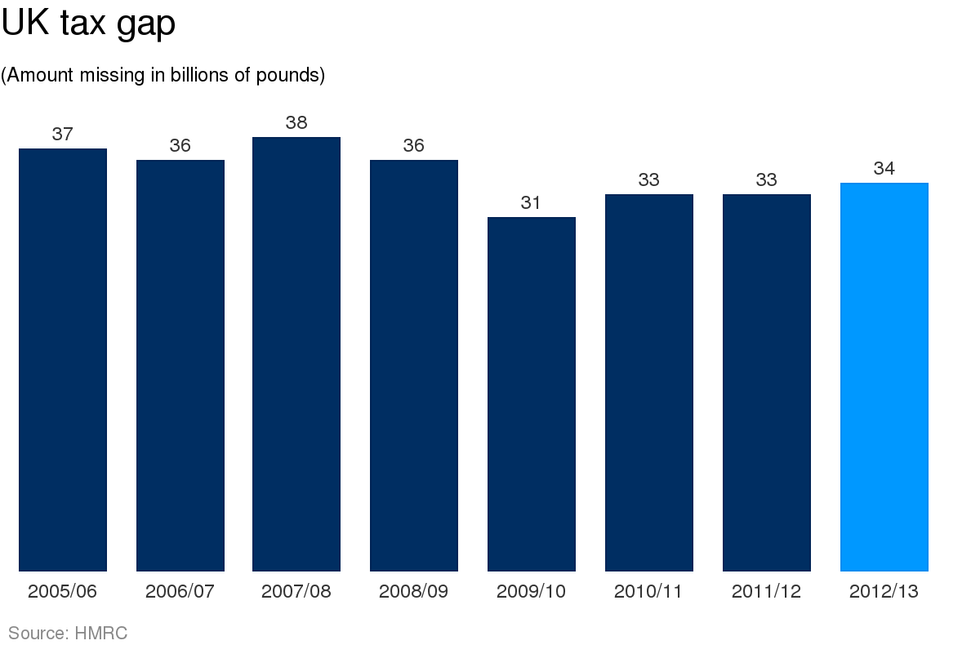

A lack of transparency in those havens means it can be hard to calculate exactly how much money is being lost but in Britain, for instance, HMRC figures show that the estimated "tax gap" - the difference between what is due in tax and what is actually paid - is 6.8 per cent of the total due, or about £34bn for the latest year with available data.

But developing countries are losing out too

Companies listed on the FTSE 100 in London operate businesses in countries all across the globe. If they avoid paying tax in those countries, the revenue services are losing out on vital income that can help to alleviate poverty and pay for vital public services - like roads that the same companies use to transport their goods and schools in which their future employees are educated.

ActionAid estimates that “developing countries lose three times more to tax havens than they receive in aid each year”.

While dodging pedestrians along Piccadilly, Edward Musosa, an activist from the University of Zambia who is visiting ActionAid, told me that pushing for reform in the country is difficult.

The companies hold a lot of power - increase taxes and they say the cost of production is too high. If they close down then it means a loss of jobs and revenue for the country.

- Edward Musosa

Nevertheless, with elections in Zambia next year, he hopes to start a similar tour back in Lusaka, the country's capital, and to make tax avoidance "an issue for all the parties".

How do they do it?

Some multinationals, because they have offices in countries around the world, can operate in one jurisdiction but divert their profits through their own subsidiaries based in havens to avoid paying the domestic rates of tax - something called "profit-shifting".

After some team star jumps to warm up, Natasha and Tom use a stash of chocolate coins to demonstrate how SAB Miller, the world's second biggest brewer, managed to minimise its tax bill.

In 2011, ActionAid alleged that the company produced many local beers across Africa but the brands were listed in the Netherlands - a relative tax haven. The African subsidiaries would pay millions in royalties to the Dutch company and ActionAid estimates they saved around £20 million in tax that way. Meanwhile, small-time retailers often end up paying higher tax rates than a company that can boast net profits of $3.6bn a year, they claimed.

SAB Miller wrote to ActionAid with this letter to strenuously deny any allegations that it engages in "aggressive tax planning". It explains that "compliance with tax laws underpins all of our corporate governance practices" and that "avoiding substantial inefficiences (avoiding double taxation, as incorporated in OECD principles) which would otherwise inherently flow from having operations which trade across borders, is a necessary and reasonable activity".

Moving on to a Starbucks near Berkeley Square, Tom and Natasha explain how the coffee company has made a "mocha-ry of the tax system that leaves a bitter taste". Despite showing investors their huge profits in the UK, Starbucks had paid just £8.6m in tax on an estimated £3bn in sales since 1998 by shifting some profits to the Netherlands in royalty payments and buying coffee beans from a trading subsidiary in Switzerland.

After a public outcry, the company announced it would be paying a "voluntary" £10m per year in corporation tax, whether or not it was profitable, and emphasised that it had always organised its tax affairs "according to the letter of the law".

While these methods used by companies like SAB Miller and Starbucks aren't illegal, many believe they are highly immoral.

How would improved tax laws help developing countries?

Not only does tax avoidance hinder development but it means countries have to rely more on international aid which often comes with clauses attached - i.e. it has to be spent in a certain way.

Aid can also be subject to fluctuation. If one party gets elected in a country they may decide to suddenly cut the aid budget, whereas tax is, or at least should be, a more consistent source of income that gives governments more autonomy.

How does the tax tour help?

Being serenaded by bagpipes outside the Tanzania High Commission

The tour, which has been running for a year and lasts about an hour and a half, points out the oft-unassuming offices of supposed FTSE100 tax-dodgers dotted across the city.

People say that 'tax is a really complicated thing that only accountants know about'.

But in an informal environment like this, people feel a lot more comfortable discussing tax, which can otherwise be quite a dry topic.

- Tom Barns, ActionAid tour guide

The engaging (and legal-team-approved) script the ActionAid team have put together certainly helps to cut through the jargon and despite feeling frustrated and angry at just how widespread tax avoidance practices are, you are left with a sense of optimism that things can be changed.

Does campaigning even work?

Yes. Barclays bank is a great example, according to ActionAid. After 53,000 people signed a petition and hundreds more wrote to their MPs, the bank's CEO Antony Jenkins (see above) announced at its 2013 AGM that it would axe its tax avoidance unit, known as structured capital markets. ActionAid believe this has positive knock on effects when Barclays clients invest in African countries.

What can you do?

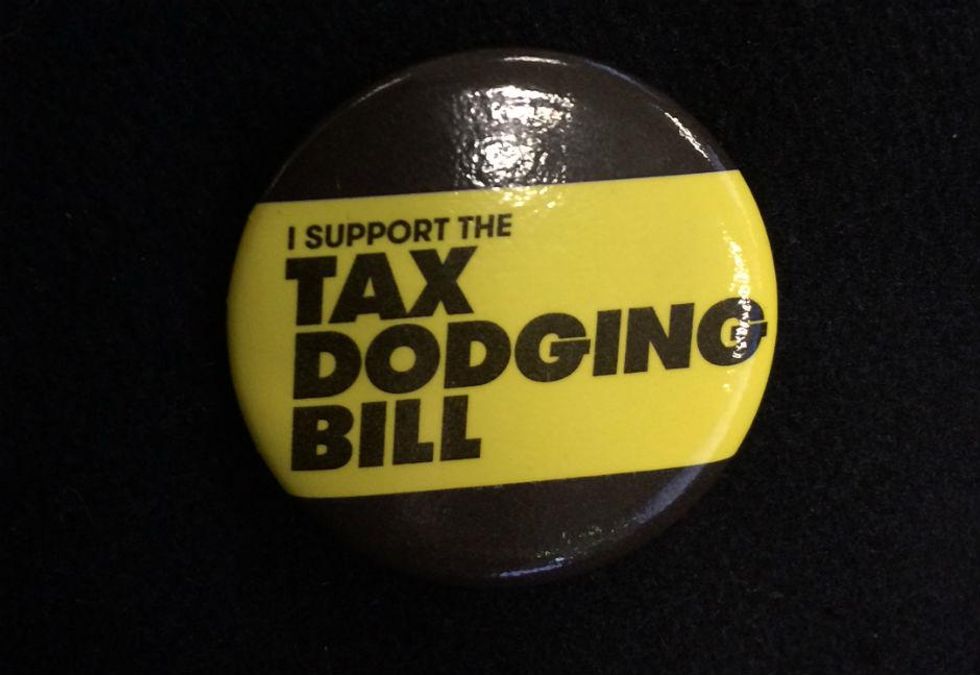

ActionAid's mission is to get all the political parties to publicly pledge to introduce a 'tax dodging bill' 100 days after the election - preferably in their election manifesto.

Rather than backing one political party we want all the parties to make a pledge so that in the case of a coalition they won't have the excuse to say their coalition partners haven't agreed to it.

- Natasha Adams, ActionAid activism officer

The tax dodging bill would make all British companies pay their fair share of tax here and wherever else they operate. Ideally it would make the whole tax system more transparent and increase punishments on tax avoidance.

To help push this through, ActionAid want as many people as possible to lobby the prospective parliamentary candidates (PPCs) in their areas to write to their party leader calling for the pledge.

You can read about the Tax Dodging Bill here, read ActionAid's company case studies here and buy tickets for ActionAid's next Show me the Money tour on 10 March here.

More: The people connected to David Cameron who are linked to tax avoidance

More: Global inequality is so bad it's almost impossible to visualise it

More: World's richest one per cent will soon own same as poorest 99 per cent

Top 100

The Conversation (0)