News

Narjas Zatat

Aug 08, 2016

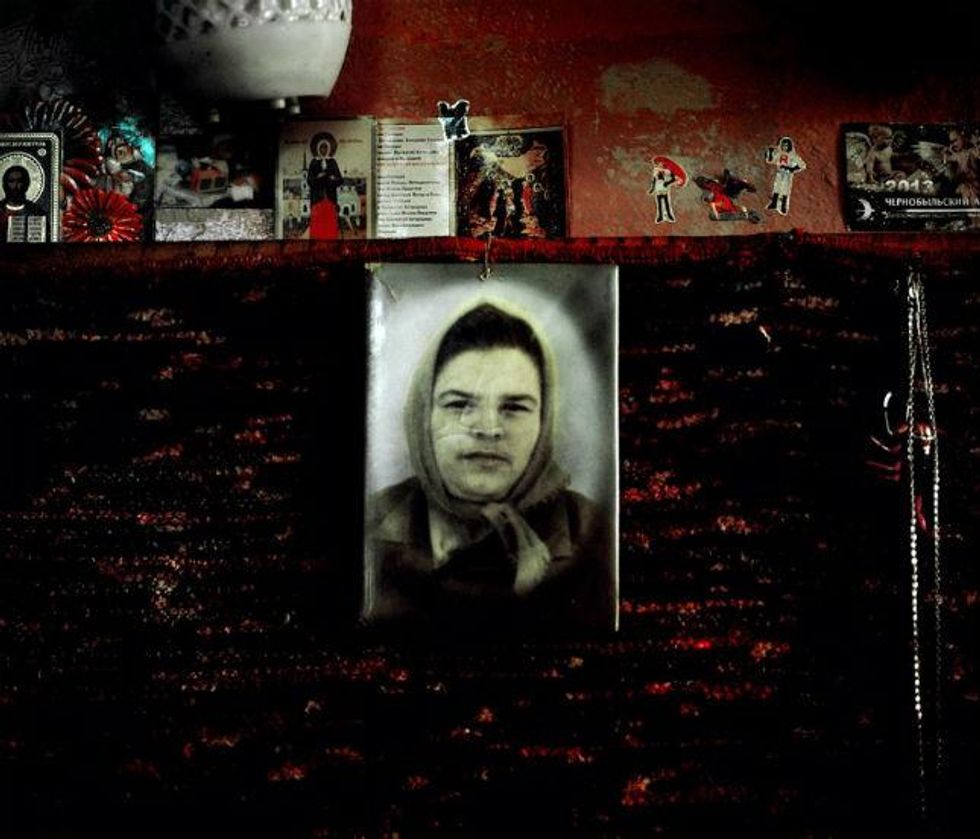

The 1986 Chernobyl disaster is a grim reminder of the dangers of nuclear power.

The incident, which was the combined fault of a flawed reactor and human error killed 30 workers and the WHO estimates it could be responsible for up to 4,000 deaths from cancer caused by radiation exposure.

Over 30 years after the event, the consequences continue to show in birth defects and an increase in thyroid cancer.

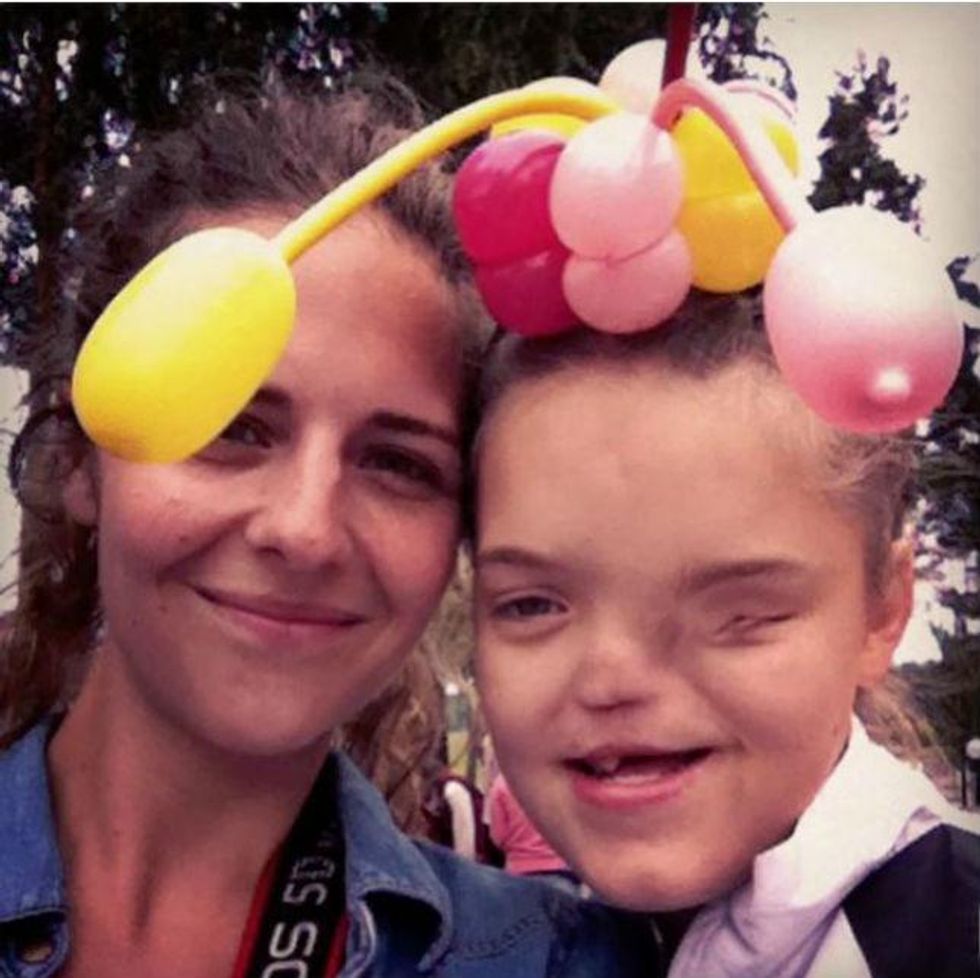

Thirty-year-old photographer Jadwiga Brontē decided to visit Belarus earlier this year to document the lives of the Chernobyl victims in government institutions referred to as “internats” – part asylum, part orphanage, part hospice.

indy100 spoke to Brontē about her work, titled 'Invisible People of Belarus':

What drew you to Belarus and the Chernobyl disaster? Do you have any personal connections with it?

I was born in neighbouring Poland, a satellite state of USSR at the time of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. I decided to go to Belarus to document the stories of horrifically neglected and abandoned children, born with mental and physical deficiencies from the aftermath of this tragic accident 30 years ago.

It’s an incredibly delicate subject, were there any issues with photographing these victims?

Issues with visual representation have been a big part of photography for a long time, especially when it comes to vulnerable people. Picturing disability is an extremely sensitive topic, which always incorporates the notion of ethics and aesthetics.

There is a reason why there are almost no photographs of disabled people nowadays; it might be because of the past approach to this topic and the huge issues with ‘good representation’ of ‘others’. Disabled people became almost a metaphor for ‘otherness.’

Through my work I want to show that disabled people are capable of studying, working, building lasting relationships and contribute to everyday society. For me the residents of the institutions I visited are amazing people, beautiful and strong. Invisible People of Belarus is a story of us, human beings.

How does the rest of Belarus treat these victims?

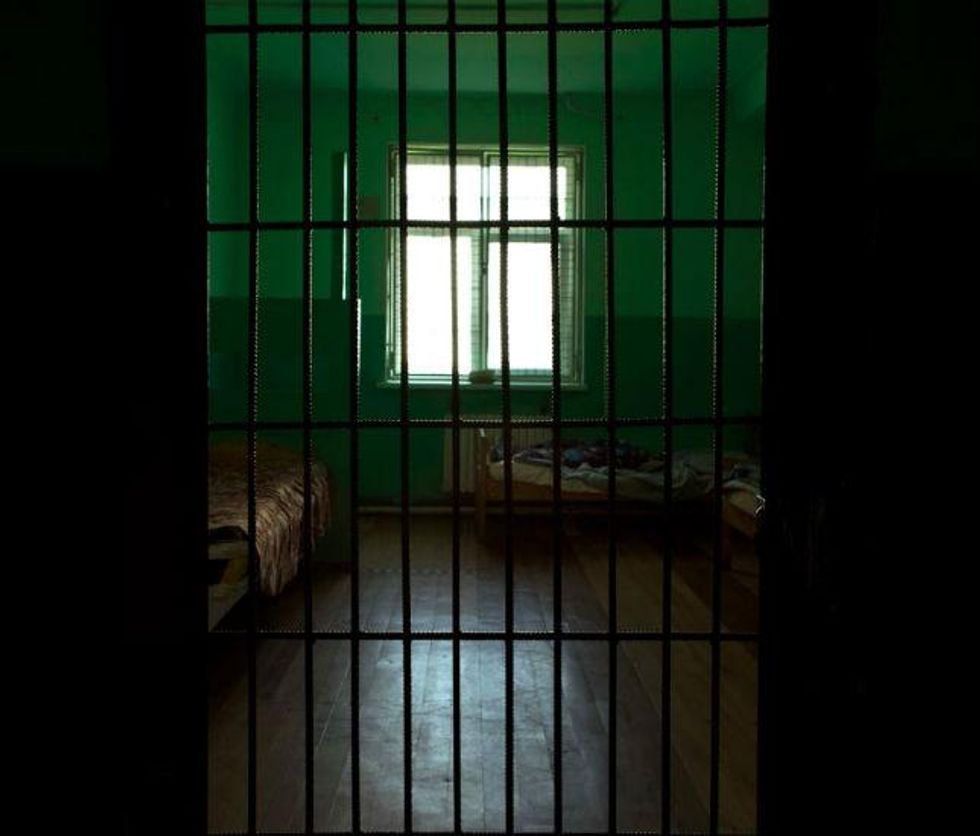

In general, disabled people are certainly still something of a taboo in Belarus, and often abandoning, or ‘giving them away’ is easier than being exiled from the local community. Mothers are told that institutions are better places for their disabled kids than home. In the past, mothers would be persuaded to give up their children and place them in the internats, nowadays they are manipulated into abortion. Belarusian people themselves are not aware of what is really going on inside these places.

What are your future plans?

I have gathered some money via Kickstarter so I will be able to self-publish first edition of Invisible People of Belarus.

The book will be written in two languages Russian and English. It is important for me that it will be available for viewers living in post-soviet countries where issues with disablism is high.

The book will include short texts from the book 'Voices from Chernobyl' by Nobel Prize in Literature Winner - Svetala Alexievitch who is an investigative journalist from Belarus.

What is more 10% of each single sold book will go towards an amazing charity.

There is no free press in Belarus, that’s why, I decided to work on this project and share it with Belarusian people and the rest of the world. What is more, the aftermath of Chernobyl and the issues with nuclear disasters are an on-going problem around the world… we cannot forget about the victims of radiation and new victims born nowadays because of the modified gene the parent carried on.

One of the most important images is called ‘Free Labour’ below - Disabled women working in a field.

Institutions are partly self-sufficient [and] patients are forced to work in fields, clean and cook.

To successfully improve the situation of the Belarusian internats, first we must change the mentality of the Belarusians. It’s in their hands to change the future of the people locked up.

All photos courtesy of Jadwiga Brontē

More: A photographer went around the world and asked people what they thought of tourists

More: The illustrations that show what life is like with anxiety

Top 100

The Conversation (0)