A private spacecraft carrying a piece of technology developed by UK scientists is due to make history as it begins its journey to the moon.

The Peregrine Mission One (PM1) – built by US space company Astrobotic – is set to become the first private probe to land on the lunar surface.

It is also slated to be one of the first US moon landings since the final mission of the Apollo programme – Apollo 17 – more than 50 years ago.

Onboard will be an instrument known as the Peregrine Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer (PITMS), which was developed in the UK by scientists from The Open University (OU) and the Science Technology Facilities Council (STFC) RAL Space – the UK’s national space lab, in collaboration with Nasa’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Washington DC.

Simeon Barber, of The Open University, who developed a key sensor on the PITMS instrument, told the PA news agency: “I have been developing the underlying technology since I joined The Open University as a PhD student 25 years ago.

“So yes, it is a culmination of lots of hard work, as well as backing from our funders.

“It is amazing to see this sensor now heading to the moon as part of an instrument led by my colleague Barbara Cohen at Nasa’s Goddard Space Flight Centre.”

The device will analyse the thin lunar atmosphere as well as find out more about how water might be moving around the moon.

For many years, scientists believed the moon was bone dry and any water detected in the samples from Apollo missions were thought to be contamination from Earth.

However, more recent missions have revealed the presence of water and, in 2020, Nasa confirmed the presence of water molecules in sunlit areas of the moon.

Dr Barber told the PA: “Various new data in the last decade has overturned the Apollo-era notion of the moon as a bone-dry place.

“We have seen hints of ice at the cold lunar poles, and suggestions of water (or the related hydroxyl molecule) globally, as well as new analyses of Apollo samples showing small pockets of water within the lunar rock itself.”

Understanding the lunar water cycle is crucial for future exploration of the moon.

Water is a key resource for sustaining a human presence on the moon – providing drinking water as well as supporting various industrial processes.

Dr Barber added: “We are interested in how these water molecules travel through the lunar exosphere (atmosphere) under the influence of day-night temperature cycles, eventually reaching the super cold polar regions where they accumulate slowly as frost or ice layers.

“This transport through the exosphere is the link connecting the various sources of water, and their eventual fate locked up in polar cold traps.

“PITMS will measure the composition and density of the lunar exosphere through the lunar day, allowing us to deduce the processes at play on the moon today, and by extension, throughout the moon’s history and on other similar planetary bodies.”

He added: “I am hoping that the measurements we make will help us understand how the gases in the moon’s incredibly thin atmosphere interact with the surface rocks and soil.

“This will be another price in the jigsaw that helps us work out how water vapour moves around the moon, and whether one day we might be able to harvest it to turn into drinking water for astronauts working in lunar bases.”

The launch window for the Peregrine lander opens on January 8 at 7.18am UK time.

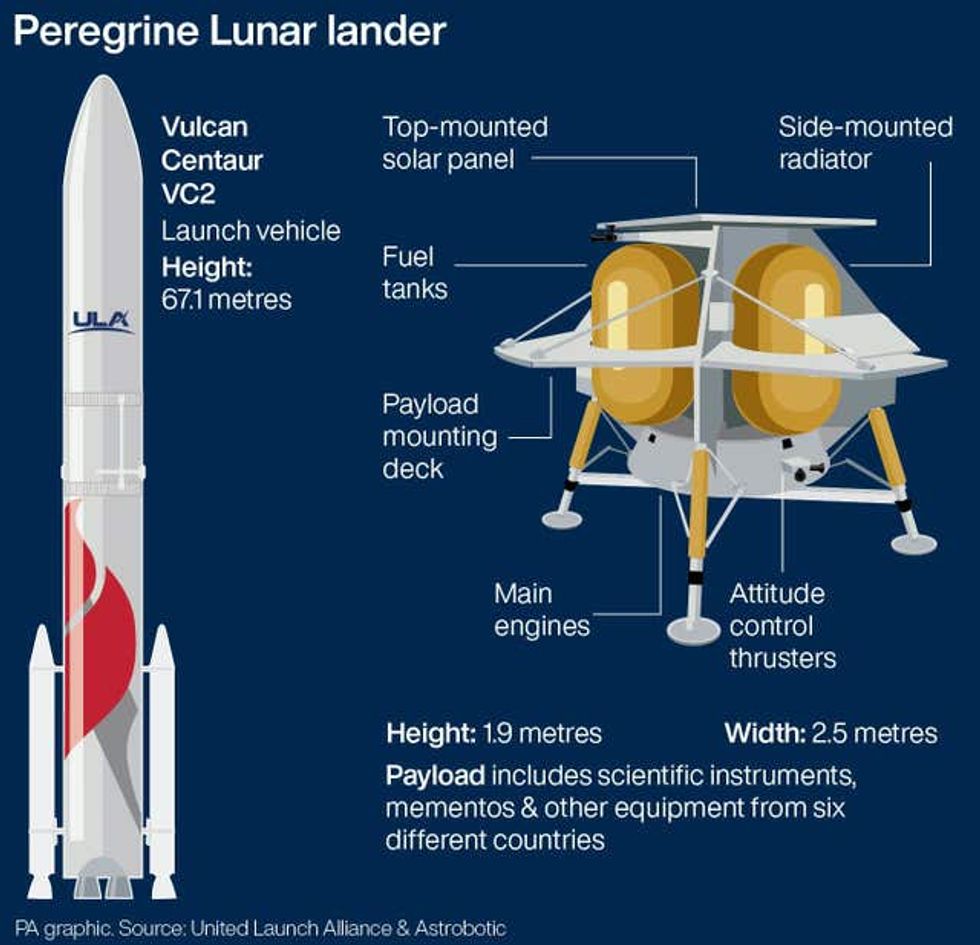

The spacecraft will blast off aboard a Vulcan Centaur rocket, built by US aerospace manufacturer United Launch Alliance, from Cape Canaveral in Florida.

It is part of Nasa’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative, which aims to involve commercial companies in the exploration of the moon.

Officials say the spacecraft could attempt a lunar landing on February 23.

Its destination is an area in the Gruithuisen Domes, a series of volcanic domes named after the German astronomer Franz von Gruithuisen.

Once it is on the surface, the Peregrine lander is designed to operate for roughly two weeks – or one lunar day.