News

Dina Rickman

Aug 20, 2014

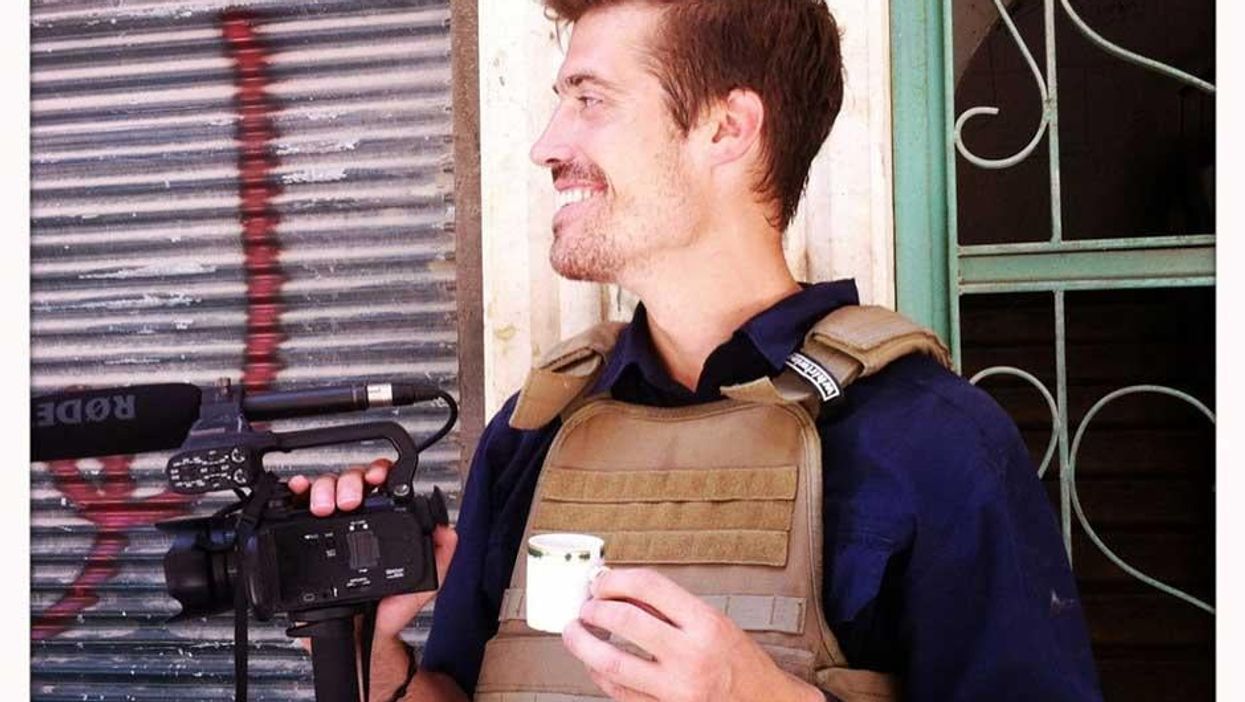

James Foley, the American journalist whose murder was purportedly posted online by Islamic State (Isis) militants last night, had given several interviews and talks about war reporting.

Notably, he spoke candidly and movingly to students at his alma mater, the Medill School of Journalism, about both his experiences of reporting and what drives him. He also spoke about his experiences of being captured in Libya in 2011 alongside three other journalists just two months before. This is James Foley in his own words:

The honest fact is when you see something really violent, it does a strange thing to you. It doesn't always repel you, sometimes, as you know, it draws you closer. Feeling like you've survived something - it's a strange sort of force that you are drawn back to. I think that's the absolute reality.

I'm drawn to the frontline naturally...The frontlines in Libya are just so dangerous.

- Speaking to students in Medill in 2011

On why he wanted to be a war reporter:

I think it's some kind of romantic notion you have about yourself, too. You want to be a writer, you want to see the world. Fiction didn't work out too well, let's try the real thing. I mean there's an amazing reach for humanity in these places, in these barren places.

We were in a prison cell with a doctor, his name was Dr Kamal Tedo [sic]. British Libyan, brilliant guy. Paediatrician from Manchester, England, originally Libyan.

He had come back with his family a few years before and had gotten involved bringing an Al-Jazeera team into one of the most dangerous cities. He kept that team alive and moving for two days during tank shelling by hiding them in mosques, hiding them in houses. I think on the third day they thought they were safe, they were captured.

- Speaking to students about in Medill in 2011

On different types of war reporting:

The one thing about the embed [with the army] is you always have a screen. There's always a screen of literally US armour, a base, separating you from the population. Do I really know the Iraqi people. Do I really know the Afghan people? Well I know an Afghan who is a translator for the US army.

- Speaking to students in Medill in 2011

On whether he would go back to Libya:

I told my editor at Global Post "I know this is crazy but I want to go back to Libya". He said "I don't think it's crazy, I think you need closure... Emotionally I am not ready to go back.

- Speaking to students in Medill in 2011

Speaking in detail about when he was attacked by Gaddafi forces and arrested in Brega, Libya, before spending 44 days in a Libyan prison:

Our plan was to see exactly what was going on. Who had this city of Brega. The rebels were saying 'we have Brega.' Other people were saying no, the Gaddafi forces have Brega. We wanted to see who had Brega and we wanted to get out there before the checkpoints had started. They had started to get organised and these are journalists - us - trying to get past the checkpoints to see what was actually going on. This is trying to trick the system already.

We get out the scout vehicle, this is the exact place we were attacked. Clare [Gillis, an American reporter who was with him] asked one teen how far Gaddafi's forces were from us. The teen said in English '300 metres'. I heard it, we all did... We all decided to get off the road.

And about coming under attack:

Two Gaddafi military pickups were bearing down on us. I remember exactly how they looked, tan pick ups, a large machine gun mounted on the back of each and filled with soldiers. Any soldier or reporter who has been under direct fire knows, the body reacts much before the mind can process what is actually happening. The mind can even present the illusion of safety. But the fight or flight instincts are in control. We pressed ourselves as close to the ground as possible... the roar of bullets was deafening, there was no getting out of this. But the corner of my mind still, in defensive mode, hoped we were in the crossfire - meaning the rebels were somewhere else firing behid us. Even more illogically I hoped that the vehicles behind us were rebels shooting that had made a mistake and would quickly stop.

I crawled forward, my video camera still rolling, towards a larger dune. Anton [Hammerl, the South African photographer with them] was stood in front of me. It was impossible to tell when he'd been hit.

When you know you have to do something or you are going to die, then you see your colleague probably dead and you get hit a couple of times you have so much adrenaline in you that I didn't even feel it... [I was in] the worst kind of shock. If you've been in a car accident and hit another car because of an error of judgement, it's like that. But it's... times what?

The next morning you wake up and you realise the worst thing in the world just happened. The worst possible thing. Anton is most likely dead and we're captured and nobody knows where we are.

Our story is a very cautionary tale. We made a lot of mistakes that day. Conflict zones can be covered safely.

- Speaking to students in Medill in 2011

It's our job. I've been covering conflicts since Iraq in 2008. I really am drawn to the drama of the conflict and trying to expose untold stories, I'm drawn to the human rights side.

There is extreme violence but there is a certain sense of trying to find out who these people really are.

- Speaking to the BBC in 2012 at fundraiser for Anton Hammerl, a colleague who died when he was captured with Foley in Libya

Journalism is journalism. If I had a choice to do Nashua (New Hampshire) zoning meetings or give up journalism, I'll do it. I love writing and reporting."

- AP interview 2011

To read more of James Foley's journalism about his time in prison in Libya, click here.

A yellow ribbon tied outside Foley's house in Rochester, New Hampshire.

More: This is how James Foley should be remembered

More: Remember James Foley for his fearless reporting from conflict zones

More: Mother's tribute to James Foley is heartbreaking and inspiring

Top 100

The Conversation (0)