News

Patrick Diamond

Jun 17, 2017

Picture:

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Patrick Diamond is a physics professor at the University of California. When asked, on Quora, why only a few people become really successful, despite many other people being equally intelligent, he had this to say.

This is an interesting question, which, as usual, means it's important, a bit vague and difficult.

The answer surely depends heavily upon precisely what you mean by “intelligent” and “successful”. I'll take a somewhat different approach and tell you about a study of scientific productivity and its implications for the question.

Of course, here “success” = productivity in scientific research (i.e. writing papers) and “intelligence” = cognitive ability relevant to doing science (i.e. basically what we think is the conventional type of intelligence,as measured by IQ tests ). Nevertheless, I believe the lessons of this study offer insights of broad applicability.

The punchline is:

- It is no surprise that there are few successful people (i.e. stand-outs). There are good reasons for this. If success requires skill in many different areas, success is multiplicative, not additive, and the distribution of success is lognormal, not Gaussian.

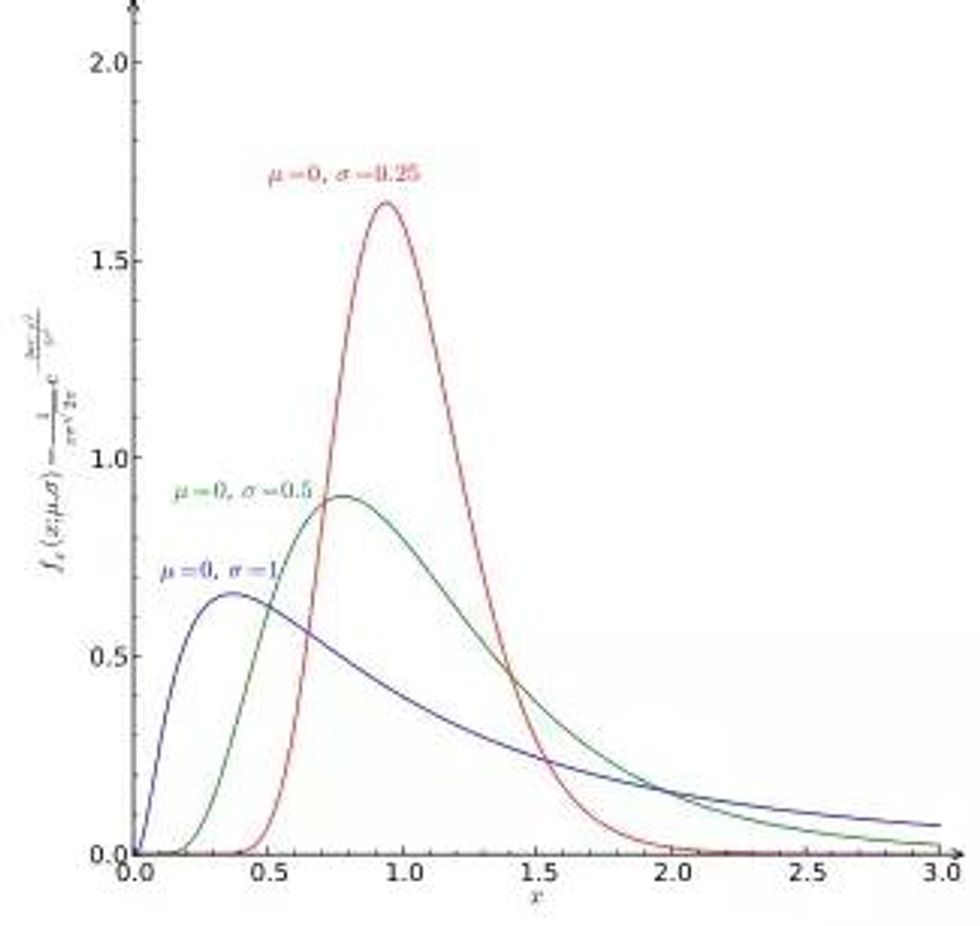

For your information, a log-normal distribution looks like this:

There is not much of a tail ... The message is that superstars are RARE.

Only a few of the multiplicative attributes are related to scientific ability. Other attributes include communication - i.e. WRITING ability - and perseverance, i.e. what are now called “grit factors”. Indeed, I suspect there are more such elements.

The story is based on studies of productivity at Bell Labs (remember them?) done by the famous/infamous William Shockley (don't disregard this just because its Shockley...), in 1957, and discussed in the great blog “Dynamic Ecology” William Shockley on what makes a person who publishes a lot of papers (and the superstar researcher system).

Shockley was interested in the answer to the question of what it took to produce papers and why so few people were so very good at it.

Following the blog, which followed Shockley (with some annotation):

Shockley suggest that producing a paper is tantamount to clearing every one of a sequence of hurdles. He specifically lists:

- Ability to think of a good problem (IDEAS)

- Ability to work on it (TECHNICAL SKILL)

- Ability to recognize a worthwhile result (EXPERIENCE)

- Ability to make a decision as to when to stop and write up the results (EXPERIENCE)

- Ability to write adequately (MY FAVORITE)

- Ability to profit constructively from criticism (GRIT)

- Determination to submit the paper to a journal

- Persistence in making changes (if necessary as a result of journal action). (TRUE GRIT – REFEREES TRY THE SOULS OF THE SCIENTIST)

Shockley then posits, what if the odds of a person clearing hurdle i from the list of 8 above is p(cleared_hurdlei)p(cleared_hurdlei)? Then the rate of publishing papers for this individual should be proportional to the joint probability of clearing each independent hurdle:

∏8i=1p(cleared_hurdlei)∏i=18p(cleared_hurdlei)

This gives the multiplication of random variables needed to explain the lognormal distribution of productivity (Shockley goes on to note that if one person is 50% above average in each of the 8 areas then they will be 2460% more productive than average at the total process).

But what I really like and take home from this paper is the hurdle model and how I find it a useful way to think about my paper writing productivity. The model says writing a paper is not about one thing. It is about a bunch of things. And – the really surprising point – all of those things count more or less equally. I think most academics have a mythos that people who are productive scientists are mostly good at #1 (coming up with ideas) and maybe #6 (writing).

I don’t think most people think about the fact that being productive is about knowing when to stop or knowing what is an important result. And especially, #7 and #8 are about rejection and dealing with rejection. Did it ever strike you that being a productive scientist is 1/4 about dealing with rejection well? It probably should – recently at a meeting, the vice president of research on our campus pointed out that the person with the most grants on campus was the person who had been rejected on the most grants. (INTERESTING...)

Another conclusion is that if you are really bad at just one factor (p(cleared_hurdlei)p(cleared_hurdlei) close to zero for just one i), it sinks your overall productivity. This is innate in the multiplicative model (it is analogous to the ecological concept of bet hedging*). Being moderately good at everything is better than great at some and terrible at others (the oft heard “I’m terrible at writing but really good at coming up with ideas” doesn’t cut it but nor does the opposite). BUT ONE NEED BE GOOD AT MANY DIFFERENT THINGS.

Of course, since success is multiplicative, the logs are additive and so the log of success follows the normal distribution, and voila – the log normal.

Logically, winners should be very, very rare.

There are a few observations which can be added to this:

- The Shockley study was done before computers, let alone the internet, and in an environment of individual PI or very small teams. Times have changed. Surely, tech savvy, ability to lead and manage teams, and online presence would enter the multiplication today, driving winners further down the tail. Has a study like Shockley's been done at Google or FB? Are the results available? (silly question..., I know).

- “Grit” seems a bit more specific than EQ. Surviving constructive criticism and the sniping of one's competitors takes real determination. BTW, the psychologist Angela Duckworth ( Department Faculty) recently got a McArthur for her work on grit.This was an excellent choice for an award!

- Writing is very important. Some things don't change... Life in Quora has its merits.

- A classic example of a “multiplicative success ” story is the famous Steve Jobs.His technical acumen needs no discussion. Less well known is that Jobs studied calligraphy,indicating an interest in,and ability for,art. Is it any surprise that a strength of Apple products was their aesthetic appeal. His business ability excellent.Finally,Jobs surely had grit-he endured many reverses during his long career,and bounced back from all of them to leave Apple valued at $7bn+. Clearly,Jobs was much,much more than a talented techie . Is it any wonder that he was one of the success stories of our time?

- The issues of luck and being in the right place at the right time keep popping up.Fortuitous timing is discussed in great detail in Malcolm Gladwell's wonderful book “Outliers”.One of Gladwell's main points is that while yes,timing matters a great deal,it is ultimately how one utilizes the opportunities which one encounters which determines the difference between success and failure.This is consistent with Shockley's first criterion-ability to identify a good problem.Opportunities and good problems are out there to be grabbed.Winners and successes find them -sadly,the ability to do so is very,very rare.

There is more to be said, but this answer is too long as it is. Non-scientist readers will no doubt dismiss me as arrogant, but I will display GRIT by suggesting this study has broad implications.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)