Sirena Bergman

Dec 03, 2020

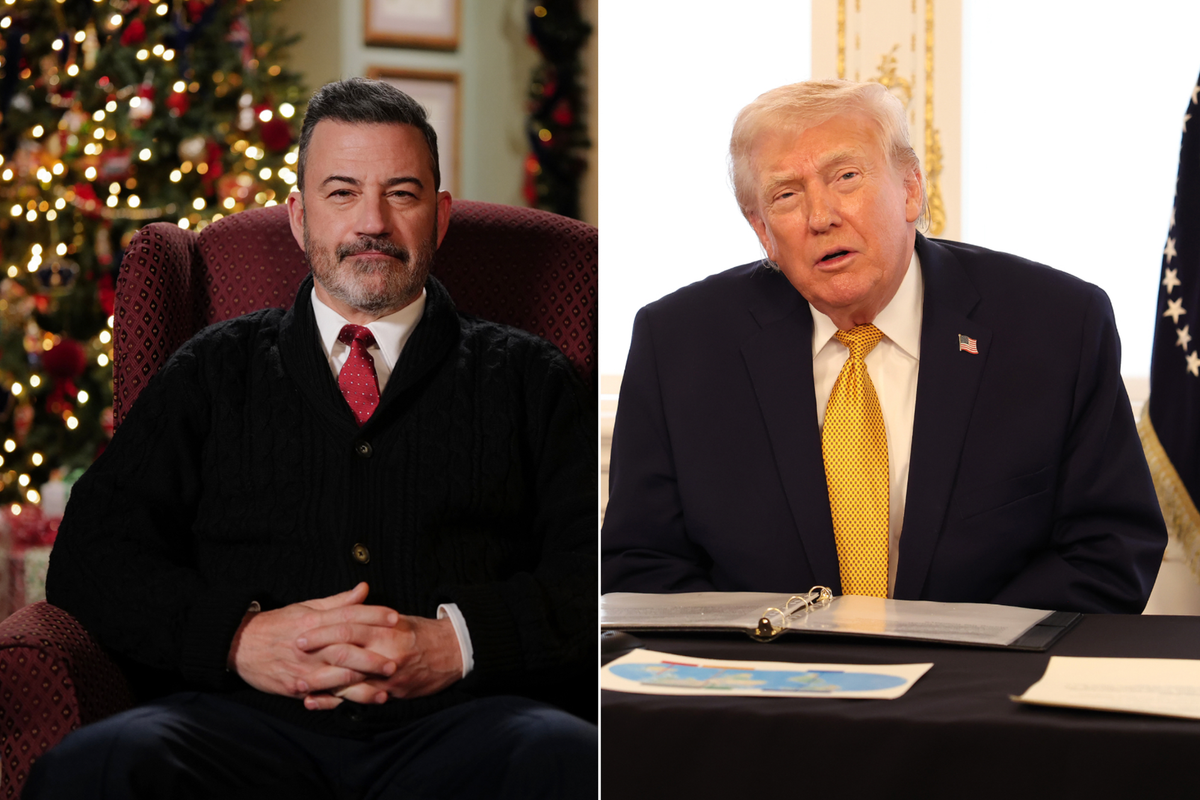

Getty Images for IMDb

Actor Elliot Page has come out as transgender in a moving statement posted to Twitter and Instagram this week.

In the post, he clearly stated that his name is Elliot and his pronouns they/them and he/him, adding: “I can’t begin to express how remarkable it feels to finally love who I am enough to pursue my authentic self.”

Page received an overwhelming amount of support across social media, from fans, fellow celebrities, wife Emma Portner and even Netflix itself, which tweeted to say how proud it was of “our superhero”, alluding to Page’s character in the popular superhero drama The Umbrella Academy, in which he stars as Vanya Hargreeves, a cisgender woman.

Despite the support, not all the response has been positive. Ignorant and transphobic remarks have been made across social media since Page’s announcement. While not surprising, this is still painful to see, and actively harmful to the transgender community, which is comprised of some of the most oppressed people by society at large.

Page himself highlighted this, saying in the post:

“The discrimination towards trans people is rife, insidious and cruel, resulting in horrific consequences. In 2020 alone it has been reported that at least 40 transgender people have been murdered, the majority of which were Black and Latinx women.”

But it’s not just outright transphobia and violence which can lead to trans people facing a less safe and inclusive environment. Microagressions born of lack of education around trans issues can be incredibly damaging.

Things like asking intrusive questions about medical treatment, using the wrong pronouns and centering narratives around sex and gender which are exclusionary towards transgender and nonbinary or gender nonconforming people are just a few examples of how seemingly harmless comments can have a huge negative impact.

In 2015, LGBTQ+ charity GLAAD put together a photoessay to highlight some of the more common microagressions trans people face. Examples of such comments include: “Did you have the surgery?” “You need to shave if you’re trying to look like a girl,” and “You understand what it’s like to be a woman” (to a trans man).

Another common form of discrimination that trans people face is what’s known as deadnaming. And that’s something we saw a lot of in relation to Elliot Page coming out.

What is deadnaming?

For many trans people, social transitioning can include adopting a new first name, often referred to as the “affirmed name”. This is often to ensure a person’s name corresponds with their gender, although for many people it can also be an important part of the process of coming out and taking ownership over their identity.

Of course not all trans or nonbinary people will do so. It’s a deeply personal choice and everyone’s experience is different. But for those who do tell us what their name is, like Page did, it it’s important that this is respected.

Deadnaming occurs when a trans person is addressed or referred to – directly or indirectly – by the name they were given before they transitioned. It often goes hand in hand with misgendering by using the wrong pronouns.

When does it happen?

Unfortunately, there are many context in which given names are used for official purposes, such as legal or medical documents. While it is possible to change one’s legal name for any reason, it can be a time consuming and costly process which not all trans people have access to.

A 2015 survey showed that only 11 per cent of trans people in the US had their affirmed name present on all government IDs.

In 2018, an investigation by ProPublica found that deadnaming can continue after death too, reporting that across the US, 74 out of 85 murder cases in which the victim was trans were conducted using the victim’s deadname. This can have a huge impact on the investigation, slowing it down in its crucial initial hours.

But deadnaming is frequent in everyday life too. Family members, friends, teachers and coworkers will often use a trans person’s deadname, even if their intention is not to cause offence.

It’s understandable that this can happen by accident, but it’s also important to remember that many trans people experience daily discrimination and harassment from a queerphobic, cis-centred society. Remembering someone’s correct name and pronouns is not a huge sacrifice for allies to make, and it can go a long way to showing acceptance and support towards trans people in your life or the public eye.

Why is deadnaming harmful?

For cis people, names and pronouns may not feel like a huge deal, but for many trans and nonbinary people, deadnaming and misgendering can feel like an invalidation of their identity.

It can also potentially out them as trans in a context where they may not want to disclose that fact.

In 2018, trans activist and actor Laverne Cox responded to the aforementioned ProPublica report with a powerful statement, writing: “Being misgendered and deadnamed in my death felt like it would be the ultimate insult to the psychological and emotional injuries I was experiencing daily as a black trans woman in New York City, the injuries that made me want to take my own life.”

Cox added that deadnaming is “an act of cultural and structural violence”.

Her feelings are echoed by a number of trans people and activists, who say deadnaming can be traumatising and triggering, and makes them feel less safe.

Christopher Reed, a professor of history and scholar of queer culture, has written that deadnaming also "inhibits efforts toward self-acceptance and integration."

What does this have to do with Elliot Page?

Following Page’s statement, his deadname was widely used across social media. This is not necessarily out of malice, but many pointed out that regardless, we can all do better.

Others highlighted the positives, including many media oulets which reported the news without deadnaming Page, instead using images of the actor and highlighting his most well-known roles to avoid any confusion.

Chase Strangiom, a trans activist and attorney with the ACLU, wrote for NBC News earlier this year:

“If you want to know (or write) about someone and then go in search of their deadname or an old picture to use or disseminate, think long and hard about why that's important to use. Your prurient curiosity shouldn't get to trump our right to dignity and respect, and we are going to assume that your self-serving desire is more about hurting and exposing us trans people than accurately describing the people we are.”

Deadnaming should never be necessary, and when a little discomfort or inconvenience is weighed up against the potential negative impact it could have on the person being incorrectly referred to, it becomes apparent that the former is always preferable.

Top 100

The Conversation (0)