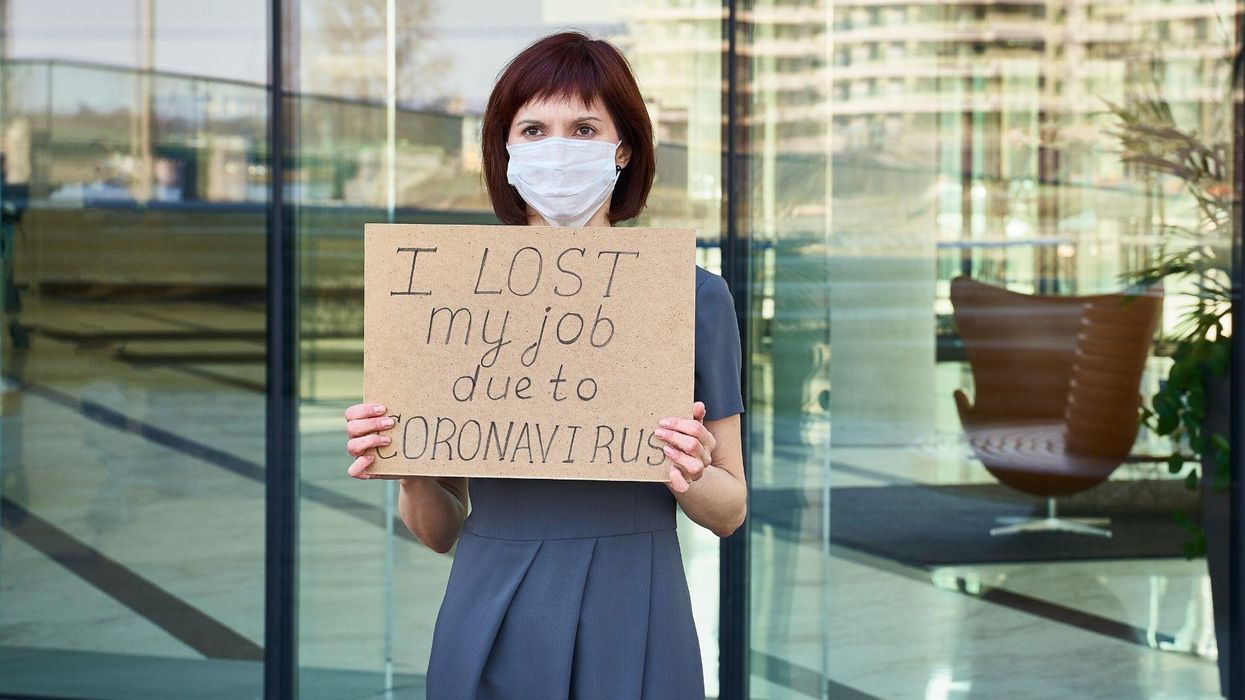

News

Moya Lothian-McLean

May 08, 2020

iStock

Reporting by Moya Lothian-Mclean

Earlier this week, it was reported that Chancellor Rishi Sunak was considering plans to “wind down” the furlough scheme that has been protecting over six million jobs across the UK. The news was greeted with anxiety – for many, the 80 per cent wage subsidy provided by the government is the only income keeping them afloat.

The Tories take a different view, with one senior source apparently telling The Times that workers were “addicted” to furlough.

But for thousands of UK workers, the removal of the furlough scheme will make no difference to their situation because they didn’t have access to it in the first place. This unlucky cohort is made up of several different groups, including people who started in new jobs after the 28 February, workers whose employers refuse to furlough them, self-employed people who went freelance after the end of the last tax year, and directors of small limited companies whose wage set-up is not recognised in the scheme.

They’ve spent the last six weeks desperately lobbying the government to recognise their plight, to little avail. Now, with Sunak apparenly preparing to “wean” the nation off the scheme altogether, despite no signs of the UK economy returning to “normal”, they feel time is running out – while their money already has.

“I feel helpless; I’m stuck 300 miles from home with no job, no permanent home and no money”

Tim Smith is one of 2.9 million people who make up the UK’s hospitality workforce.

When lockdown was announced, Tim was two weeks into a new job as a live-in chef in a Cornish restaurant, a role he’d travelled 300 miles from his home in north Wales to take up. March is supposed to mark the start of the season for hospitality workers who depend on tourism to pay the bills. Instead they’ve been faced with a complete shutdown of the industry.

Tim was no exception. On 24 March the restaurant he worked at shuttered its doors and staff prepared to depart. Tim was “nervous” about how they’d manage the situation, he says, but not overly concerned... yet. Days earlier he had watched Rishi Sunak announcing the Job Retention Scheme, allaying some of his fears. But then his boss called her employees into a meeting. It wasn’t going to be that simple, she told them.

Quickly, it emerged that the scheme had a gaping loophole; workers were only eligible if they were in employment before 19 March. Tim was – he started his job on the 8 March 2020. But the scheme only recognised a person as being on payroll if they were also paid before the 19 March. And Tim was one of the thousands of UK employees who received his wages monthly. His boss had no choice; she couldn’t furlough him. Suddenly Tim was left with no income whatsoever.

“I ran out of cash on the 19 April,” he says. “I was going every other day not eating; a stranger on the internet ended up sending me money just so I could go and buy some food”.

Tim’s thankful to his employer, who’s let him stay rent free in on-site staff accommodation. Along with 2 million others, the chef applied for Universal Credit, as advised by the government, but won’t receive his first payment until 9 May. That payout – which is supposed to last claimants a month – isn’t even equivalent to a week’s wage for Tim.

Being trapped hundreds of miles away from his family, with no sign on the horizon of any financial support beyond Universal Credit, is taking its toll on Tim, who says he’s desperate to work.

“I’ve got bills to pay and no idea how long this situation is going to last,” he says.

I used to work in care; I got out of it because of the cuts. It’s ironic that if I’d stayed there, I’d be working right now but instead I’m holed up in a tiny little room having to ask my mum for a tenner for the first time in my life. It’s had a noticeable effect on me mentally and I don’t have work to distract me from it.

I don’t even know if there’s going to be a job for me to go back to. I feel helpless; my family isn't in a financial position to help me and I can’t go back home because it’s £200 for a train ticket and there’s nowhere for me to isolate even if I managed to.

Joining campaign group New Starter Justice has made Tim realise the scale of those left behind by the government’s scheme, he says.

So far, NSJ have garnered support for their cause from over 60 MPs, with 46 signing an open letter penned by the group, but no action has been taken by the government to update the JRS. Tim is frustrated and frightened, for himself and other new starters he’s in contact with, like a pregnant young woman whose breadwinner partner can’t get furloughed. Every day, he says, it feels like someone else “falls by the wayside”.

Nothing about the situation makes sense to him.

“My employer wants to furlough me,” Tim says. “I got paid on the 28 March, like thousands of others. We’ve suggested the government moves the scheme’s cut off date to the end of March; they’ve already made changes so we know they can.

“I’m not the sharpest tool in the drawer but it seems very simple; I’ve got the contract, the payslip and my job registers on my HMRC account. I heard Steve Barclay, the Brexit secretary, said there had been “trade offs” in order to keep the scheme simple. We aren’t “trade offs”; these are real people he’s talking about”.

“I was eligible for the government scheme but my employer refused to furlough me”

Going into March, Katie* was still employed as a copywriter at the marketing agency she’d been working for over six months. As the threat of Covid-19 loomed ever closer, her employers seemed unconcerned; they told clients they had “geared up” for a work-from-home scenario.

The only nod to a pandemic were the hand-washing signs that suddenly appeared around the office – despite Katie’s bosses not providing any soap to accompany them.

Then, a week before lockdown, Katie and eight of her co-workers were made redundant and given a week’s notice, which they were required to work. When the furlough scheme was announced, it “seemed like a godsend” she says. Immediately, Katie emailed her boss, asking if she and the other workers who’d been let go could now be furloughed. No response.

A day later, Katie’s boss rang to discuss some details about her redundancy so she asked again if they’d be furloughing staff.

“‘We’ve made our decision and you’re redundant’ was the reply,” she says.

Katie tried to reason with her employers, telling them they could fire her again once furlough ended and that she only wanted the 80 per cent of wages provided by the government, but they refused to budge, citing phantom “costs” of having to make staff redundant at a later date or the “lack of clarity” around the scheme.

In desperation, Katie reached out to her local MP and a business expert but was told that there was nothing they could do to help – the government hadn’t introduced any legal requirements for businesses to furlough workers. The scheme Rishi Sunak had promised would save workers from bearing the brunt of the economic impact of Covid-19 was “optional”.

Katie is now staring at a ticking clock as her savings trickle away. Due to assets she can’t access, she’s not eligible for Universal Credit but is going to try claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance. Buying groceries is now a source of severe stress. To make matters worse, her former employer has now furloughed at least one worker but still refuses to extend the same treatment to Katie and others.

“I’m not sure what to do next,” she says. “I’ve got a raft of bills to pay. I’ve never claimed government support before and if this was a “normal” situation, I would live frugally on my last paycheck as I looked for a new job. But in this scenario I’ve no idea when a regular income will pop up again. I applied for supermarket jobs but they were all taken”.

Bill repayment ‘holidays’ aren’t an option yet; with no idea of when her income will return, Katie says she’s too afraid of sinking into future debt. The situation is becoming unbearable, she tells me.

“I’ve cried several times in frustration,” she says. “The financial support from the government is there but I can’t access it. I don’t know how much longer I can do this for. Even before lockdown I struggled with anxiety; now it’s overwhelming”.

“At first I thought we’d been forgotten – now it feels deliberate”

Two years ago, accountant Wendy Brown set up her own limited company. Business was good; Wendy was the sole employee but she was proud of what she’d built, especially as a single parent to two young children juggling childcare with work. But when lockdown started her major contract was pulled and her income slashed by 50 per cent overnight.

Wendy thought she’d be covered by the measures announced to protect self-employed people because she completes a self-assessment tax return and owns her company. But then she had a “lightbulb moment” and realised that technically, she wasn’t self-employed – she was classed as ‘employed’ within her own company.

While this meant in theory she was eligible to furlough herself, it emerged that dividends (a payment companies can make to shareholders if it has made a profit, even if the shareholder is the director) weren’t included in the amount available for furloughed employees. Directors of LTD companies tend to take lower PAYE pay and higher dividends as their wages.

“Generally people take a small monthly PAYE amount so there’s a regular income and then dividends when there’s a profit,” explains Wendy of the practice, which she says some mistakenly class as tax evasion. “And we pay corporation tax before those are taken”. Overall it saves about “£40 a month” she estimates.

Wendy also realised that if she furloughed herself, she would no longer be allowed to work at all.

Furloughing was the better option financially but it’s the viability of the business after this. I can’t sit there and undertake no work for god knows how many months and expect to be able to come out the other side.

Sole traders are allowed to work, and they get a grant in June to help with the loss of income. But a director of a limited company isn’t. I think they see us as these massive organisations when, in reality, about two million of us are micro-entities.

With no savings or pension to rely on, Wendy has been forced to apply for more government help on top of her existing childcare tax credits. But she’s heard nothing and in the meantime has had to turn to family for financial support. Currently, she’s considering a loan. Despite being well aware of the risks they pose, she feels there’s no choice.

“It seems our only option is debt,” she says. “These bounce back loans have great interest rates but if that work doesn’t pick back up, we’ll be drowned in debt”.

As an accountant, Wendy’s already thinking ahead to the likely austerity that will face Brits after the pandemic ends – and the impact that will have on those already left behind by the government now.

“We're going to be affected in terms of interest rates and taxes and all these sorts of things to help the economy recover, but we're not being supported now,” she says.

Wendy has joined the #forgottenLTD campaign which is lobbying for the government to finally offer help to struggling directors of small limited companies by offering support in line with what they’ve extended to sole traders. At this point, she thinks the government is well aware of their situation but is “intentionally” leaving them behind. The emotional impact has been “devastating”, says Wendy, who prides herself on her integrity. “To be seen as a tax dodger… it hurts”.

“We just want a scheme that’s fair,” she says. “They say we’ve saved tax, fine, don’t give us 80 per cent, give us 75 per cent, whatever. But we’ve paid our taxes and contributed.

"They think we’re these big guys in our suits, with savings and offshore accounts and it’s just not the case. We’re micro-businesses”.

*Names have been changed

Top 100

The Conversation (0)